On February 1st, 2007 a group of members of the street community, along with advocates, formed a tent city in Downtown Olympia.

We not only changed the course of dozens of lives, but we changed the conversation around homelessness and our community’s response to it.

In the fall of 2006, I had been on staff at Bread & Roses (B&R) in Olympia for about three years. Founded in the early 80s, B&R was a Catholic Worker house, inspired by Dorothy Day’s work with the poor and marginalized in our society.

In Olympia, the organization had grown to encompass the original house (on 8th Ave between Boundary and Central), used as a community gathering place and where the staff lived. We all got room and board and a small monthly stipend in exchange for our work. Next door to the staff house, there sat a duplex that housed our women’s shelter. A dozen or so women who needed a place to get back on their feet could stay there as a part of the community, with an advocate assigned to them to help them along the way. We also had an advocacy center in Downtown Olympia that was a place folks could drop in and warm up and work with an advocate on whatever barriers they were facing. Above all else, we wanted it to be a safe harbor. Inside those walls, you could shed the pressures of the world and just be. And when you were ready for it, help was available.

It had been three years of witnessing the direct impact of homelessness in the lives of people whom I had come to care for and love very much. Tormented daily by predators, police, and policies – all things compounding to make it nearly impossible to recover from the cycle of homelessness. A friend compared it to being stopped on the side of the freeway, and every time you tried to pull out into the lane, a car would come whipping by, and you’d have to stop again.

Resources were scarce and getting scarcer.

Our city council took a conservative, “pro-business” approach. Getting rid of homeless people was the goal, as opposed to helping them to improve their lives. This trend culminated in the Summer of 2006 in the form of a Pedestrian Interference Ordinance that would strip people’s right to gather in public spaces – namely, our sidewalks – during certain times of the day. This followed other ordinances that targeted camping, car-camping, and panhandling, among others. Our so-called compassionate liberal bubble was proving itself to be anything but that.

I remember how powerless it felt. I was tired of watching my friends die for no reason. People were sad, scared, angry, and they didn’t know what to do. Typically, they would have just kept taking their lumps without putting up a fight. People were resigned to being relegated to second-class status.

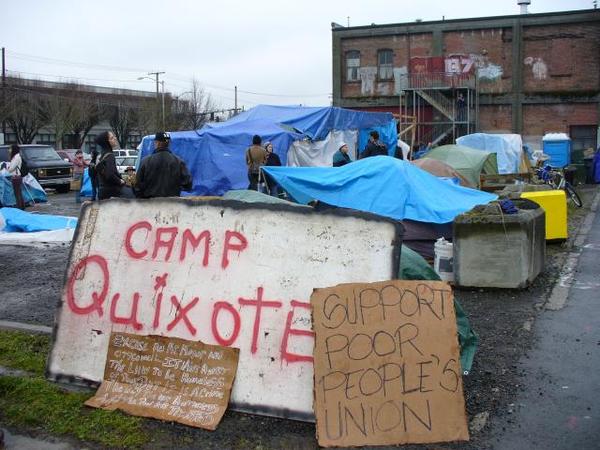

Tim, a friend who had been houseless off and on most of his life, was angry and wanted to do something about it. A group of us had had movie nights. We would watch political or historical documentaries and movies and discuss how they applied to what was happening locally. During one of these movie nights, the conversation began about political action in response to the ordinances. That night we laid the groundwork for the birth of what would become known as Camp Quixote – I thought of the name as a show of solidarity to a group in Paris who was involved in a similar tent city protest. We also chose a name for our newly conceived group, the Poor People’s Union (PPU), which would serve as the camp’s organizing body.

The first meeting of the PPU was on a Saturday afternoon at the Bread & Roses Advocacy Center. It drew (probably because of the free coffee and pizza we made available) about two dozen people. We laid out our vision to create a tent city where folks could live with the safety and security that a tight-knit community provides and work toward a permanent location. They would be free of the pressures of the social service system, able to recover at their own pace.

We didn’t know how people would respond going into that first meeting, and I don’t think any of us were quite expecting the response we received. People were excited. There was a fire behind their eyes. New hope for self-determination. A feeling of value, that their lives were more than their current condition and that it was ok to demand more – ok to be outraged by a community that shoved them aside.

We officially formed the PPU. We made membership cards and pins to wear. Everyone paid one dollar in dues – some of us wanted to let anybody join whether they could pay or not, but the street contingent members overruled us. They wanted to buy in and own this thing.

We started having general meetings every Saturday where we would plan every aspect of the camp. We formed subcommittees to plan camp rules, security, site selection, kitchen, communications, and camp design, among others. We elected leaders for each committee, and they would give progress reports at the general meetings on Saturdays. Only members of the Street Contingent – folks who would be residents of the camp – could hold leadership roles. The rest of us took on responsibilities in support of and directed by the leadership team.

Eventually, the Site Selection Committee determined that the ideal location would be a parking lot downtown owned by the City. As a committee member, I researched multiple public and private places before recommending a site. We had various reasons why we ended up where we did. Our fight was with the City of Olympia, so locating on city property made sense. The lot was also in the Downtown core, on one of the busiest streets in the county. That provided multiple benefits, but mainly exposure. Thousands of people would drive by every day that otherwise might not have known the camp existed. Many got curious and pulled off to see what was up. Many of those people came back with supplies or to volunteer. That was huge for the campers’ morale, and that community support would prove critical later on as well.

Once we picked the site, we decided that February 1st, 2007 would be the move-in day (also the day that the ordinance was to take effect). That gave us only a couple of months to finish our preparations. Supplies needed organizing and materials gathered. We spent those final two months busily staging materials and methodically crafting the action plan for move-in day.

When February 1st rolled around, we set our plan in motion. The first step was to set up the tents. We laid out pallets and tarps then erected and waterproofed tents. Simultaneously, I coordinated the delivery of two port-a-potties, and the kitchen crew was setting up the kitchen tent and prepping for dinner. By the end of that first day, we had over twenty tents set up, and we all were able to have a makeshift meal together.

Day two brought more people and more tents to set up. The committee in charge of camp layout took on the newcomers and gave them jobs in the camp. Positions included a rotating 24-hour security detail, kitchen crew, camp maintenance, and neighborhood clean-up. Neighborhood clean-up was essential to the campers, who wanted to be good neighbors. They devised a daily litter patrol to tidy up the blocks surrounding the camp.

On day three, materials arrived for the common house, located in the center of the ring of tents. It would serve as our gathering place for camp meetings, meals, and nightly entertainment. The construction team built out the frames for the walls and roof, and just like an old-fashioned barn raising, we all helped pull them upright and hold them in place while others hammered everything together. While this was happening, the kitchen crew was prepping a colossal chicken dinner, using chicken donated by Top Foods and veggies donated by community members.

That night was one of the most joyous nights I’ve ever experienced. We ate together, danced, laughed, and enjoyed each other’s company inside of this great hall that we built together. I’ve never felt more alive than I did that night. Seeing those faces that for years had been weighed down by the pressure of life on the streets, the constant fear, stress, humiliation – all of that lifted away. You could see their inner beauty shining through, what was inside them, what could be drawn out of a person if we simply choose to bring people in rather than push them away.

The response to our presence from the surrounding community was, for the most part, positive. Ben Moore’s, a restaurant located on the same block, brought us a huge pot of hot soup every day – and a “We heart Camp Quixote” sign hung in their window for years after. We were inundated with donations. Blankets, tarps, sleeping bags, warm clothes, food, and much more were coming in steadily. Parents would bring their children down to visit, and we would have conversations with them about homelessness and why the camp was there.

The City of Olympia, on the other hand, was not as supportive. They informed us that we were trespassing and were subject to arrest and confiscation of our belongings. From that point forward, there was a looming sense of certainty that the camp could be swept at any time.

We quickly formed an intelligence-gathering committee to monitor radios and scout out locations where police stage for raids to have the earliest possible warning to get people out who couldn’t risk arrest or be at risk if the police used force, especially tear gas. The City Council instructed staff to notify us that we were trespassing and must vacate the property, or they would send in OPD to disperse the campers.

The local media, The Olympian, were equally unsupportive. They ran an editorial urging the City to break up the camp and arrest those who remained.

We knew that the threat of a police raid weighed heavily on folks, so we started making a plan to move the camp. We began exploring many options, including moving to a different lot downtown or finding a space hidden out in the woods somewhere. I will note, however, that the campers were unanimous that giving up was not an option.

One member of our extended support network had the idea of asking a church, specifically their church, the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Congregation (OUUC), to allow the camp to move to their property. The OUUC board was having a meeting the following evening, and our supporters volunteered to attend and request sanctuary on their property. When the news came in that the OUUC Board had decided to grant us refuge, it hit the camp and spread fast. People were ecstatic, inspired, and relieved – this was a victory.

We made plans to move the next morning.

At 5 am, with everyone except the security detail sound asleep, the Olympia Police Department, with the City Manager in tow, descended upon the camp in a loud, showy display. They had tipped off The Olympian newspaper, so a reporter and photographer were there to make sure the city got its photo op.

The pre-dawn raid shocked the campers, some of whom fled and abandoned their belongings. Those who stayed were shaken and scared from the violent, unexpected, and abrupt awakening. A few of the people who fled weren’t seen for weeks because they were afraid that OPD was after them.

As morning broke and the shock subsided, our volunteers arrived to help us move and get the new camp set up.

A couple of weeks later, the congregants at OUUC voted to allow the camp to stay for an extended period. Work began to create structure and formalize the relationship.

The City of Olympia and Thurston County Health Department got involved in regulating health and safety at the camp. The Panza Board was formed to support the camp in its journey. To guide not to govern it, an idea that has held firm throughout the years.

Years later, as a member of the Olympia Planning Commission, the camp came back into my life. The question before us was whether or not to allow a permanent homeless encampment inside the City of Olympia. Regulations at the time only allowed for a temporary camp that had to move every 90 days. I convinced my fellow commissioners to vote in favor of my motion to recommend the change to our City Council. I was proud to be part of this next step for the camp. A vision that we created all those years ago, of having a permanent site with little houses and a small farm, was becoming a reality.

Years later, I stood on the empty lot that would be Quixote Village. I watched my dear friend Kevin, who had overcome so much, plunge his golden shovel into the rocky soil, breaking ground and initiating the final phase of the Camp’s evolution. I could not have been prouder. I fought tears as I relived in my mind those nine days in February of ’07.

Those beautiful people of Camp Quixote – so often shoved aside and kicked around – decided one day they’d had enough. They showed bravery and strength beyond words—vigor and resilience in the face of turmoil and constant threat. But more than anything, they taught me the power of grace. That you should show more grace than people deserve because you change the world by being better, not by slamming doors in peoples’ faces.

The camp succeeded and is living its dream today because we allowed the campers to lead us.

That I got to play a small part in the camp’s formation, and its continued success is something that I will never forget. I will always keep with me the lessons I learned from this experience – especially that the power of love and community will always persevere. If we draw on the strength of community and act with reciprocity and magnanimity when called upon, no challenge is too great, and no goal is unachievable.

Given the challenges we face and those that lie ahead, I’ll be drawing from lessons learned at that little camp 14 years ago.